LISTEN NUTTALL GANNON REVISED (30 Minutes)

Nutrition Today has just published something extremely rare, and possibly unique – it’s a peer-reviewed science study that checks out the claims of a low-net carb food product. And this science study indicates that one low-net-carb “protected starch” product may not live up to its claims. The new study, by Minneapolis VA Health Care System and University of Minnesota researchers Mary Gannon and Frank Nuttall, challenges the claims of Dreamfields Pasta that their pasta does less to raise blood sugars than regular pastas do. In their advertising, Dreamfields states that a serving of their product has only 5 grams of digestible carbohydrate, compared to the roughly 40 grams of carb in regular pasta. Dreamfields also states that those carbs become sugar in the bloodstream much more slowly than carbs from traditional pastas. Gannon and Nuttall have done a randomized, controlled, double-blind study of 20 non-diabetics that found no difference between how this “low carb” pasta affects blood sugar levels, compared to regular pasta. They say that they got interested in this topic because they were seeking a low-carb pasta for their diabetic patients who miss the taste of pasta, and they were hoping that the Dreamfields product would be work. They were surprised at how much Dreamfields pasta did NOT live up to its claims. Transcript follows. See the end of this article for links to other discussions about Dreamfields.

Nutrition Today has just published something extremely rare, and possibly unique – it’s a peer-reviewed science study that checks out the claims of a low-net carb food product. And this science study indicates that one low-net-carb “protected starch” product may not live up to its claims. The new study, by Minneapolis VA Health Care System and University of Minnesota researchers Mary Gannon and Frank Nuttall, challenges the claims of Dreamfields Pasta that their pasta does less to raise blood sugars than regular pastas do. In their advertising, Dreamfields states that a serving of their product has only 5 grams of digestible carbohydrate, compared to the roughly 40 grams of carb in regular pasta. Dreamfields also states that those carbs become sugar in the bloodstream much more slowly than carbs from traditional pastas. Gannon and Nuttall have done a randomized, controlled, double-blind study of 20 non-diabetics that found no difference between how this “low carb” pasta affects blood sugar levels, compared to regular pasta. They say that they got interested in this topic because they were seeking a low-carb pasta for their diabetic patients who miss the taste of pasta, and they were hoping that the Dreamfields product would be work. They were surprised at how much Dreamfields pasta did NOT live up to its claims. Transcript follows. See the end of this article for links to other discussions about Dreamfields.

Dr. Frank Nuttall, what do you think of products that advertise that they’re low “net” carb because you can deduct an especially high amount of fiber in the product, or “protected carb” from the total carbohydrate. What do you think of that?

FRANK NUTTALL: I’m not quite sure what the question is. Now fiber, which can also be referred to as non-starch carbohydrates, is supposedly a non-digestible carbohydrate and so it goes through the small intestine into the colon and is fermented by bacteria. We do not gain any net food value from the fiber, so what do you mean by a net carb?

SHELLEY: “Net carb” products are often advertised as containing far fewer carbs than the “total carb” count. Yet, people who have a weak pancreas or insulin resistance often report that, even though a product’s “net carbs” are low, eating them spikes their blood sugars. That is, their blood sugars go up far higher than a person would expect if those so-called fiber carbs or “protected carbs” weren’t being digested. For instance, Dreamfields Pasta is marketed as being far lower in carbs than typical pasta.

FRANK NUTTALL: Well the Dreamfields pasta product contains fiber, and because of the fiber content and some other ingredients, it has been assumed that the digestible carbohydrates in that pasta product, will not be digested. It’s also been reported by the company that while the glucose resulting from the digested carbohydrate does get into the blood, it comes in more slowly and so it would not raise the blood glucose as much. However our data in normal people indicates that the blood glucose response is basically the same with Dreamfields Pasta as with traditional pasta. So there was no net value in regards to lowering the blood glucose in these individuals if they ate one starch versus the other.

MARY GANNON: My name is Mary Gannon What I would like to tell you about is a study that has been published in Nutrition Today, in which we looked at the effect of ingestion of Dreamfields Pasta compared to a regular pasta in normal individuals. Each subject ingested both types of pasta. The pasta was prepared according to package directions, and we found absolutely no difference in the glucose response in these normal subjects when they ingested either type of pasta. Glucose responses to both pastas were identical.

SHELLEY: How much time did you give people between eating each pasta, and what did they eat ahead of time?

MARY GANNON: They were to eat a normal dinner the night before, and be fasting for 10 to 12 hours before they came in for the study. The studies were done about one week apart. The pasta was ingested just as the pasta. Individuals could put salt and pepper on it but no butter, no cheese, and it was eaten as a breakfast meal.

SHELLEY: That does not sound very tasty, but they did eat it?

MARY GANNON: They did. They indicated that it would be much better if they had some sauce on it. The other interesting thing is that they were not able to distinguish between the two pastas. The study was blinded to both us as the investigators and to the individuals volunteering for the study. So the only person who knew which pasta was being prepared was the person from the food service department who was cooking the pasta.

SHELLEY: How much of pasta did they eat each time?

MARY GANNON: The servings were calculated to be the identical amount of pasta.

SHELLEY: So you put the same number of grams of pasta on each plate for this study. One time, your tests subjects ate regular pasta, where the “Total Carbs’ are the carbs–which was about 50 grams of carb. The other time, they ate the Dreamfields pasta, which has roughly the same number of total carbohydrates as regular pasta, but Dreamfields claims that you can subtract the vast majority of the carbs, because the company says it has a special process that makes those carbs hard to digest.

MARY GANNON: That’s what the package advertisement says. The label on the package indicates that this amount of pasta will have fewer digestible carbohydrates, and they refer to it as a lower glycemic index product. Although we are not particular fans of the glycemic index concept, the concept is that if it has a lower glycemic index, that amount of pasta would raise your blood glucose less than that same amount of regular pasta.

SHELLEY: When you say “they,” say their product is low glycemic, who is “they?”

MARY GANNON. The manufacturers of the Dreamfields Pasta. The advertising on the package.

SHELLEY: Does the package say it’s lower glycemic pasta, or does it say the total digestible carbohydrate is lower?

MARY GANNON: I don’t remember off the top of my head. I do have a package if you want me to go get it.

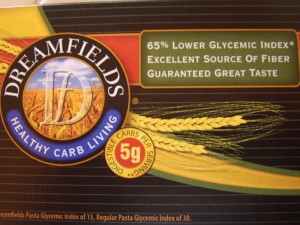

SHELLEY: Okay, this package on the front says, Dreamfields Healthy Carb Living. Digestible carbs per serving – 5 grams. 65% lower glycemic index. The food fact label says the total amount of carbohydrate listed for a serving is 41 grams. Then there’s dietary fiber of 5 grams and the soluble fiber is 3 grams and the sugar is one gram. I’m rather confused by how these numbers add up to only 5 grams of digestible carb per serving. What am I missing?

MARY GANNON: As I understand it, the process of how this is manufactured is patented, and this process makes much of the regular carbohydrate non-digestible carbohydrate.

SHELLEY: Yet they say it’s only 5 grams of digestible carb per serving, when normally it would be a 40 or so gram of carbohydrate per serving. So I would assume, IF the manufacturers are correct, that their pasta would cause blood sugars to rise less than regular pasta does.

MARY GANNON: The way that we got involved in this in the first place, is we were very intrigued by this, and we were looking for products that we could incorporate into our low biologically available glucose diet. We have found in our Type II diabetic subjects, those still able to produce insulin, they have a very good improvement in blood glucose control when they eat foods that have a low level of biologically available glucose diet. So we wanted to incorporate this product into that diet because people were missing carbohydrates.

SHELLEY: So you felt that your patients, your clients, would be more compliant with a low-carb diet, if they could have some good, tasty pasta that did not raise their blood sugars.

MARY GANNON: Yes.

SHELLEY: And you heard about this product and you hoped that it would work!

MARY GANNON: Yes. That’s exactly right.

FRANK NUTTALL: That’s correct.

SHELLEY: You didn’t have an axe to grind. You had some people to feed.

FRANK NUTTALL: Yes.

SHELLEY: No axe to grind. People to feed, and you wanted to feed them some pasta! And you were looking forward to this working.

MARY GANNON: That’s right, and we tried on several occasions to contact the company to get their primary data upon which this claim was based. Dr. Nuttall called them several times, our research dietician, Heidi Hoover, called them several times. And we were referred to their sales department, I think. We never did get the primary data upon which this claim was based. All we wanted was the primary data upon which this claim is based. That’s what we were interested in. So, we naïvely decided to test the pasta on ourselves and see what happened.

SHELLEY: Do you mean that you, Mary Gannon, and you, Frank Nuttall, decided as scientists and researchers, what the heck! You’ll eat some pasta and test your own blood sugars!

MARY GANNON: Yes, that’s right.

FRANK NUTTALL: Correct.

SHELLEY: Did you, one day, eat the Dreamfields pasta, and another day you ate the regular pasta?

FRANK NUTTALL: Yes, that’s what we did. And we were not aware which pasta we were eating. But I must say that the acceptability of the product by us and others was very good.

SHELLEY: So when it comes to taste, you gave the Dreamfield Pasta and A+.

FRANK NUTTALL: At least an A.

SHELLEY: You’d need a little butter on it, or sauce . . .

MARY GANNON: Yes, we were not allowed butter or sauce. Just pasta, salt and pepper

SHELLEY: And in your case, what did you find when you checked your blood sugars?

MARY GANNON: The responses of our blood sugars to the two products were identical

SHELLEY: Was the timing of your blood sugar response in any way different between the Dreamfields and the regular pasta? After all, Dreamfields is supposed to be a lower glycemic load pasta.

MARY GANNON: The timing was identical. We were very surprised after doing this test, and since this was just a test on ourselves, we decided we had to include more people. And so, we set about to design a formal study and have it approved by the Internal Review Board process, and go through the formal application process which we did. We did study a number of other individuals, 20, and just like in this new study, we had it randomized, cross-over, blinded, meaning neither we as the researchers, nor the people we tested, had any idea which pasta was which. Only the person cooking the pasta knew which one was which.

SHELLEY: Now you had a study earlier this year that was formally withdrawn. Do you want to explain the reasons why it was withdrawn?

MARY GANNON: The reason it was withdrawn is because when we did the study on ourselves, we didn’t get IRB approval for the results we found on ourselves, because we didn’t think we needed it.

SHELLEY: You mean that you, Mary Gannon and you, Frank Nuttall, did not get Internal Review Board, approval ahead of time, to use the data from both of you in the study numbers?

MARY GANNON: We were just eating food and sticking our fingers.

SHELLEY: And since you are both scientists and researchers, and Internal Review Boards generally are checking to see whether the study will be safe for a person-off-the-street-to-do. That is, IRBs are often double-checking to be sure that being part of a study won’t surprise a research subject or confuse him or her in some harmful way, you figured that as scientists, you didn’t need an Internal Review Board okay to include the data from each of you?

MARY GANNON: That’s correct.

SHELLEY: Since you included yourselves in the first study, the IRB said, “that doesn’t fit the rules, and the study must be withdrawn

MARY GANNON: That’s right.

SHELLEY: Now, you’ve just redone your study, and this time, you first got Internal Review Board approval for every one of the new people you recruited for that study. Did the results change this time through, or were the results identical to your previous results?

MARY GANNON: The results were identical. There was no difference between the glucose responses to the two pastas.

SHELLEY: Did the Dreamfields pasta company talk with you about the methodology of either the previous study that was withdrawn or this new study?

MARY GANNON: Yes, the president of the company came out to see us along with the person who I believe owns the patent process. They came to see us, I think it was, a few months ago.

SHELLEY: Were they smiling?

FRANK NUTTALL: No! The other person that Dr. Gannon is referring to is the gentleman who formulated the product. They initiated the conversation, and we invited them to come here and discuss this with us. Because we indeed wanted to clarify the issue of why our results did not correspond with what we anticipated, based upon the construct of the pasta and the information on the package.

SHELLEY: Did they believe the results you were getting, or were they skeptical?

FRANK NUTTAL: That’s hard to answer. I am not sure whether they were skeptical or not, but they were very defensive. They wanted to convince us that their data had indeed shown what they advertise on the package. And we sort of got back to the same issue as before, that is, we originally wanted to see the primary data upon which this pasta is being publicized as being salutary for people with diabetes in order to be able to eat a pasta product that won’t raise their blood sugar as much as a traditional pasta does.

SHELLEY: Dr. Frank Nuttall, in all this conversation with the Dreamfields Pasta group, from the standpoint of a scientist, did you hear any possible reason why the results of their data might be different from your results?

FRANK NUTTALL: No. I didn’t hear anything to convince us that the product performs the way they have advertised. They wanted to assure us that they have had sent this to an institution that does these types of studies and that every batch of Dreamfields Pasta, produced, is tested for its ability to cause less of an increase in blood glucose than one would anticipate, and would be compatible with a low-glycemic index product.

SHELLEY: What is that institution?

FRANK NUTTALL: We don’t know the institution. They described it as an institution that’s in Florida, that routinely does these kinds of studies.

SHELLEY: Now, Dr. Frank Nuttall, this is very confusing to me, because Dreamfields Pasta is standing by their claim that their product works the way they say it does, and it’s been tested by an institution that validates how it works, but they won’t say who the institution is?

FRANK NUTTALL: I don’t remember whether they did or did not. We were mostly interested and had anticipated that they were going to bring data with them, that would convince us that their product, because of the fiber content and the way the fiber is incorporated into the starch in the pasta, would result in a much lower blood glucose response than with the traditional pasta.

SHELLEY: Did anyone who is expert in the science of their studies come with them to explain the studies?

FRANK NUTTALL: No they did not.

SHELLEY: Now Frank Nuttall and Mary Gannon, you both are scientists. That means you like data. You like information, and you had this conversation where the head people at Dreamfields Pasta came and talked with you. And they referred to the science that shows their product performs the way they claim, and they said the science was good. But they wouldn’t give you any details about that science?

MARY GANNON: What they emphasized was that all the batches of their product had been tested and it was tested on many individuals, hundreds as I recall, rather than the few individuals that we have tested. So the impression that you could be left with is that our data may not be as comprehensive or as valid as theirs because we did not study of many subjects.

SHELLEY: How many people did you test for your newly published study?

MARY GANNON: Twenty.

SHELLEY: Did the responses of your 20 test subjects vary a lot or was there a general trend that was similar?

MARY GANNON: When the data are averaged there is absolutely no difference in the trends, but of course there is a little bit of variation as you would expect with different people.

SHELLEY: But for each person, was their general response to each pasta similar. That is, the blood sugar response of person A to Dreamfields Pasta, was the same blood sugar response as when person A ate regular pasta?

MARY GANNON: Yes that’s correct. It was the same.

SHELLEY: Well, if half your test subjects had gotten very different responses to Dreamfields Pasta vs regular pasta, it might make sense that, in a larger data set, you would see even more variation. But if, out of all those 20 people, they each got pretty much the same blood sugar response when they ate Dreamfields versus standard pasta . . . well, what would happen with group of 200 or 2,000 people.

MARY GANNON: I would expect that the overall similarity between their blood glucose response to Dreamfields and regular pasta would be even tighter and the response curves would be superimposable. Ours are nearly superimposed over 20 subjects

SHELLEY: This is like hearing one group talking from the moon and the other group talking from Mars. It’s very different stories that we’re hearing from your research and from the Dreamfields Pasta people.

MARY GANNON: We still very anxious to see their primary data because it’s puzzling to us as well. These people are very convinced that their product is an excellent product. They feel that they have scientific data to prove it. I can understand why it is confusing to you, looking at this. But we also think that our data are very very defensible. Our data is very reproducible and we don’t understand what would account for the different between our results and theirs.

SHELLEY: This raises a number of concerns for people who actually are diabetic, who have the problem called insulin resistance, where their cells don’t respond properly to the insulin signal. Or for people who have a weak pancreas that simply doesn’t produce enough insulin to deal with sugar. You tested regular people who have a stronger pancreas and whose cells respond normally to a load of blood sugar coming from a food such as pasta. I would think that diabetics would probably have a bigger problem, and have more risk of damage, from a product that they THINK is keeping their blood sugars low, when it might not be. There’s a real potential for harm if they consume a product that they trust to keep their blood sugars low, when in reality, the product doesn’t.

MARY GANNON: That’s a possibility. And of course, we would love to reproduce this study in other groups of people — such as people who are called carbohydrate intolerant and in people with Type II diabetes, for instance. But we just haven’t had the resources to do that.

SHELLEY: As far as you know, how many studies, independent of the manufacturers who claim they’re making low-carb products – how many studies have been done independently to check out these product claims, like you’ve just done with the Dreamfields pasta?

MARY GANNON: We are not aware of any other studies. We did literature searches, of course, before we submitted our paper for publication, and we didn’t find anything.

SHELLEY: Were you just searching on Dreamfields pasta, or low-carb pasta, or low glycemic, or net carb products?

MARY GANNON: As I recall, we were searching on low glycemic, and anything that we could find in the literature on foods with a direct comparison on one food to the other.

FRANK NUTTALL: You need to understand, we were not familiar with the term “net carbohydrate.” That’s not in our lexicon. What we talk about are digestible and non-digestible carbohydrate.

SHELLEY: What I see in magazines and product advertisements are phrases such as this one on the Dreamfields package label: “Total Digestible Carbs” or “Net Carbs” or some other indication that the amount of carbs per serving of the product is claimed to be low, even though in a normal product, the carbs would be higher. Products that claim to have an unusually low amount of digestible carb, such as low carb breads and low carb pastas, are huge market right now, and these claims are advertised in Diabetes magazines, and they’re advertised in low-carb living forums, and body builder magazines, and you’re telling me that it doesn’t look like there’s been much independent research done, to test these claims by the manufacturers.

FRANK NUTTALL: We’re not familiar with these products. Our goal was to include foods in a diet that we refer to as low biologically available glucose diet, for people with Type II diabetes who are not receiving insulin. Because if you reduce the digestible or absorbable glucose in the diet of people with type II diabetes, we’ve found that you can rather dramatically lower the 24-hour glucose values in these individuals. And since starches are basically 100% glucose, we were very much interested in a starch product that would not raise the blood glucose as much as with a typical carbohydrate or starch containing food, because of an impairment in the digestibility of the starch. And we were particularly interested because the sensory value, that is, the acceptability of the Dreamfields product was very good. It was very similar to that of standard pasta. So it would be, for us, a highly desirable product to include in the diet.

SHELLEY: You were hopeful this Dreamfields Pasta would live up to its product claims.

FRANK NUTTALL: Absolutely.

SHELLEY: You were disappointed when it didn’t?

FRANK NUTTALL: I don’t know if we were disappointed. I would say we were surprised and could not understand why it did not perform the way we thought it might perform, based on the product advertising.

SHELLEY: I’m thinking about how people whose health depends on limiting their carb intake, might eat a product like this and, if their blood sugar goes up, wonder why. I’m wondering whether those people might assume that it’s not the product making their blood sugars go up. Instead, based on the package advertisement that the product is low carb, he or she might blame themselves for their blood sugars going out of control. It might lead that person to give up trying to keep blood sugars in control . . .

FRANK NUTTALL: We would like to have more information from the company in regards to their claims and what we found. And, if there is an adequate explanation, we would certainly like to be able to hear this and potentially accept it, if there is an adequate explanation. We can only comment on what we did and what we observed.

SHELLEY: Who funded your study – the first one, that got withdrawn, and the second one that just got published in Nutrition Today?

FRANK NUTTALL: It has been supported by the Veterans Administration, since we are employees of the Veteran’s Administration. (SHELLEY’S NOTE – Frank Nuttall adds that these findings are from he and Mary Gannon and do not represent the veterans administration official stance in any way.)

SHELLEY: I hear you saying that as scientists here, you decided to devote some of your resources and your labs to checking out this issue. Did the National Institutes of Health help you with funding?

FRANK NUTTALL: No, they did not.

SHELLEY: How about the American Diabetes Association?

FRANK NUTTAL: They did not. But we did not apply for funding from either of those sources.

SHELLEY: I can’t help but wonder about magazines and other groups that get a lot of funding from advertisers of this kind of “low carb” product. What does it mean for these groups to be letting advertisers of these “low carb” products pay them money to promote their “low carb” claims, when it sounds like there hasn’t been much independent research to check whether these products perform as advertised?

MARY GANNON: I really don’t know how to respond. There are the financial issues and the political issues, and all of these sorts of things. It’s a very a very complex problem.

SHELLEY: For other discussions about Dreamfields Pasta, check out this 2005 David Mendosa – mostly supportive review, 2011 Diet Doctor, mostly critical review, January 2012 Jimmy Moore discussion of Dreamfields

Has anybody asked Dr. OZ what he thinks ?

I for one would like to know !!!

The manufacturers claim it’s important that their pasta not be overcooked, that is, served al dente. I tried it and found BGs were slightly lower, but not enough to warrant eating it.

I have been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome which includes hyperinsulinium. I love pasta and was raised on it, and I was diligent in trying whole wheat, corn, quinoa, gluten free, and low-glycemic pasta, but was unhappy with the texture and sometimes the taste. When I found Dreamfields pasta I was thrilled and between 2005 and 2012 ate this pasta, shared it with friends, and sang it’s advertised virtues and my perception of it’s taste and texture with anyone who would listen. And then I after I was taken off metformin and I wasn’t feeling well I decided to check my blood sugar every half hour up to two hours after eating Dreamfields–and my sugar went way over 140 at the two hour mark–which I had been able to maintain most of time. So, as Shelley questioned above, yes, I blamed myself, I thought that I was doing something wrong and could not figure out what was going on. I can only assume that the only thing that saved me from getting worse between 2008 and 2012 was the metformin. thank you Dr.’s Gannon and Nuttall for caring enough about your patients to actually test products before recommending them.